Professor of Political Science & History Ira Katznelson – DT015

Dean’s Table Podcast Episode

Listen Now

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:00:44 — 139.0MB)

Stay alerted

If you enjoyed today’s podcast, consider subscribing using your favorite podcast player and never miss a future episode!

About the Episode

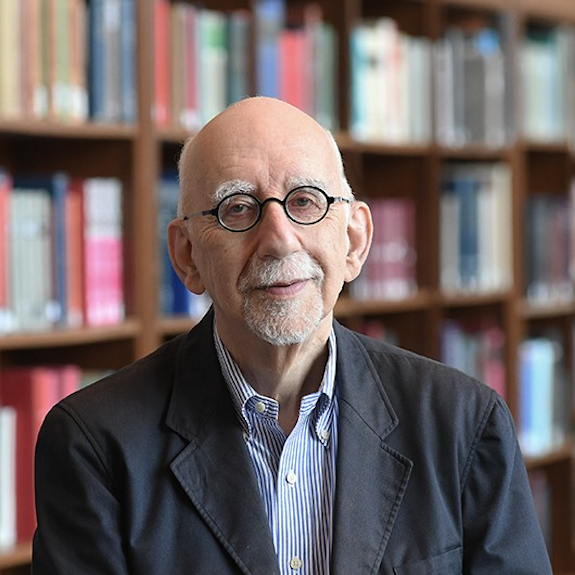

Ira Katznelson is the Ruggles Professor of History and Political Science at Columbia University. A prolific scholar and one of the nation’s leading social scientists, Ira’s work has covered a broad range of questions in the field of American politics, political history, political theory, comparative politics, and the study of race and politics. His contributions to the discipline of political science are deep and wide. Ira has twice served on Columbia’s faculty. He has also taught at the University of Chicago, served as Dean of the Graduate Faculty at the New School for Social Research, has been elected to the Presidency of the American Political Science Association, led the Social Science Research Council as its president, and most recently, Ira served as Interim Provost of Columbia University.

In this episode, Professor Katznelson talks to Dean Harris about how he decided to cross the Brooklyn Bridge to attend college in Morningside Heights, how he decided to pursue the study of history in graduate school, but has centered his intellectual career in the discipline of political science. I also invited Ira to reflect on his longstanding engagement with the study of liberal democratic societies and liberalism more generally.

Today’s Guest

Ira Katznelson

Ruggles Professor of Political Science and History

Professor of Political Science & History Ira Katznelson – DT015

Podcast Transcript

Ira Katznelson

Intro music

Ira Katznelson is the Ruggles Professor of History and Political Science at Columbia University. A prolific scholar and one of the nation’s leading social scientists, Ira’s work has covered a broad range of questions in the field of American politics, political history, political theory, comparative politics, and the study of race and politics. His contributions to the discipline of political science are deep and wide. Ira has twice served on Columbia’s faculty. He has also taught at the University of Chicago, served as Dean of the Graduate Faculty at the New School for Social Research, has been elected to the Presidency of the American Political Science Association, led the Social Science Research Council as its president, and most recently, Ira served as Interim Provost of Columbia University.

In this episode, Professor Katznelson talks to Dean Harris about how he decided to cross the Brooklyn Bridge to attend college in Morningside Heights, how he decided to pursue the study of history in graduate school, but has centered his intellectual career in the discipline of political science. I also invited Ira to reflect on his longstanding engagement with the study of liberal democratic societies and liberalism more generally. Ira, welcome to The Dean’s Table.

Ira Katznelson: Thank you. Great to be here.

Fredrick Harris: Let’s, let’s start, I guess, in essence, in the beginning. Uh, you’re a New Yorker by birth, a Brooklynite, uh, the child of immigrants who immigrated from Eastern Europe to the U.S. after World War I. What was it like for you growing up in New York City? Um, you grew up in Flatbush, Brooklyn, right?

Ira Katznelson: I did, um, from the age of four and a half or five my, uh, initial period was in Northern Manhattan and Washington Heights. But that was just through nursery school. From kindergarten onward, I was in, in Brooklyn, um, as you say in Flatbush. It was a very happy childhood, but a complicated one in ways that I didn’t then understand. Um, my parents, uh, as you noted, uh, were immigrants and they were deeply, deeply grateful for the opportunity to be in the United States, especially as Jewish immigrants, um, during the period of the Hitler regime and especially during the Second World War. Um, I only learned later that, um, significant numbers of, uh, both sides of the family, uh, did not survive the war, um, uh, willfully killed, um, and there was, therefore, a kind of, um, soft sadness, um, not directly communicated, but indirectly communicated, um, in the household, which, um, gave me a sense of appreciation for the world we were in, but also a degree of, uh, watchfulness or wariness, uh, not taking anything exactly for granted.

Fredrick Harris: Right, right. So, so you remained in the city to attend college at Columbia. Um, what drew you to Columbia and what was your experience like as a student during one of the most turbulent periods in American history, the 1960s?

Ira Katznelson: Well, I was drawn to Columbia, I think, through a small number of extraordinary high school teachers. Um, I attended a, uh, Jewish day school, the Yeshiva of Flatbush. In the morning, all our instruction was in Hebrew, in the afternoon, in English, uh, in secular studies. And I had extraordinary teachers both morning and afternoon, and they provoked in me and many others, uh, zest for reading, uh, ideas and difficult questions. And as I looked at, um, university college options, um, I only applied to three places: my “safe school” was Brooklyn College nearby. I applied to Cornell and to Columbia. Um, at that moment I thought that a number of other options or potential options, Princeton and Yale, first amongst them, uh, were not going to be very hospitable to someone with my background. So I, I aimed at, uh, Ivies, um, that I thought would be more welcoming, but also incredibly, uh, interesting and potentially challenging. And that’s what I found.

Fredrick Harris: Right, right. So, um, I understand too, that when you came to campus to interview for admissions, something happened on the way to campus. You didn’t lose the shirt off your back, but you lost something else. What was that?

Ira Katznelson: Well, um, uh, I arrived an hour early for my interview, um, bit nervous, and I used to, I wasn’t a great athlete, but I used to pitch, um, in the summers, uh, in a informal league and I asked someone, um, is there a ball field nearby? And they said, “Yes. In, in Morningside Park.” Um, so, in I went looking for the baseball field, but I was unfortunately surrounded by, uh, four young people who, um, uh, took my sport jacket, my outer coat, um, money from my wallet and, uh, a high school ring. Um, so I ended up arriving, um, to my interview in Low Library, which is then where the, uh, admissions office for the college was located. It’s now the Visitor’s Center in Low Library. Um, and, um, when I came in the, uh, person who greeted me said, “Well, where’s your coat? It’s January, it’s cold out.” I said, “Well, I’ve been robbed.” And my, my interview, uh, for admission consisted of being consoled by the Dean of Admissions, um, Henry Coleman, who later went on to a deanship, an associate deanship in Columbia College. Um, many years later I was a faculty speaker at a reunion weekend. And there was Hank Coleman who I’d come to know when I was a faculty member. And, um, I asked, I went up to him and I said, you know, “Hank, something’s been bothering me for, for decades.” Um, uh, and I started to tell the story and he said, “That was you?” I said, “Yes.” And he named the date. And he said, “I told them, ‘Take him. He’ll never come.'”

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: So that’s how I got to Columbia.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter] So here we are.

Ira Katznelson: And, and I don’t have a clue if I would’ve been admitted-probably not- um, uh, if this untoward event had not happened.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter] So, how important was Columbia’s Core Curriculum to your development as a student and your development later as a scholar?

Ira Katznelson: I think it was unevenly important. Um, uh, I had a marvelous teacher in what was then called Humanities now, Literary Humanities, um, Angus Fletcher, who was a kind of- before his time, a kind of postmodern reader of texts. And I, I understood every third word he uttered, but he was absolutely fascinating, riveting, and I couldn’t wait to get to class. My CC experience, however, and I won’t name the name of the instructor, was just the opposite. On day one, the instructor arrived, and this was my first class at Columbia, um, we used to do CC and humanities in freshman year together. Um, he said, quote, it’s an exact quote, “Young men,” we were all men. Um, “You don’t wanna be here and I don’t want to be here. So let’s make the best of a bad thing.” Well, this was a catastrophe and, um, a dozen of us in the room, uh, decided to self-organize and we did a reading group, um, of CC for the first term. The second term, I shifted to another instructor, but, uh, that was a good experience. Excellent. And then Art Humanities, and Music Humanities had a profound impact on my life. Um, if I had another life to lead, I would want to be an art historian.

Fredrick Harris: Huh.

Ira Katznelson: Um, thanks, really, to- to that class.

Fredrick Harris: So to our listeners who are not familiar with Columbia, uh, CC means Contemporary Civilization” so that’s a, a required course for undergraduates here. So, um, you just named, um, uh, one or two professors, um, what professors at Columbia was- were the most influential?

Ira Katznelson: Well, I think number one on my list was the great historian, Richard Hofstadter. Um, I had the great- the privilege, it was an enormous privilege- of writing a senior thesis under his watch. Um, it concerned the race riots in Chicago after the First World War in 1919. These essentially were, um, assaults on African Americans, starting at the beach and then spreading to trolley cars and neighborhoods by, uh, assaults on African Americans by whites, who were very unhappy with what they thought was a kind of uppity behavior of, uh, post-war African American communities. And, um, the privilege wasn’t just the chance to work with one of the great scholars of his time, uh, but the fact that we met weekly for, uh, for an hour, the first hour, he would, um, review what I had done on my thesis, and the second half hour, we would talk about contemporary events, including the unfolding 1960s, whether about Vietnam or civil rights, uh, and the like, and it was, you know, an invaluable, um, exchange for me. I should, should add that the very first day I saw Professor Hofstadter, he, um, he said to me, “If I teach you one lesson, uh, it is to write, uh, without waiting to finish your research. And each week you will bring me five pages of rough draft and we’ll look at them.” And I did that my first, the next week. Um, he took my five pages and started to read them back to me. Um, and as he was reading, he took his reading glasses off and said, now, still in the first paragraph, “Surely, Mr. Katznelson, there’s a more felicitous way to make that point.”

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: Um and I, every time I write, I hear Professor Hofstadter telling me to be more felicitous, but the, you know, I had a number of incredible teachers, I would say the, the second who influenced me the most was political sociologist Juan Linz, who moved to Yale, uh, shortly after I graduated, uh, Juan was an emigre from, uh, uh, Spain, um, was deeply interested in the conditions that, uh, make liberal democracy more likely, he taught comparative political sociology. It was a graduate course that I, with audacity, um, enrolled in, in my third year, um, we would meet at 10 o’clock on a Friday morning in Fayerweather Hall, um, it was meant to stop at noon, but it didn’t, it always went over, and then he would invite the class to lunch. So, in effect, we had four or five hours each week with Juan Linz, uh, reviewing fundamental literature in, uh, political science, political sociology, political history, um, uh, most of it, 20th century literature, beginning with Max Weber, to contemporary empirical work. And I think it was that course, uh, plus the Hofstadter experience that, um, shaped my subsequent ambitions, um, including an unwillingness, uh, to define myself, even then, fully as political scientist, political sociologist, or historian, but to find interesting questions about liberal democracy, um, both as, uh, someone who cares deeply about its central principles of rule of law and rights and consent, but also someone prepared to be, um, a critic, um, as necessary. And these, this double-whammy lesson I learned really from, uh, teachers Hofstadter and Linz.

Fredrick Harris: So, this must have, uh, influenced your decision about graduate school, because you went on to study history, get a doctorate in history at Cambridge University in the U.K., but you also had an opportunity to work with, um, the great political scientist, Robert Dahl, speaking of Yale.

Ira Katznelson: Yes.

Fredrick Harris: Um, who established the pluralist theory of democracy. Instead, you decided to go into the discipline of history. Why did you decide to attend graduate school in history rather than political science?

Ira Katznelson: [Laughter] Well, the word ‘decide,’ um, implies a kind of, um, willful, thoughtful, considered strategic choice. Um, it wasn’t that. Um, I, I applied to Yale for graduate school and was lucky enough to get a fellowship because I wanted to work with Robert Dahl. I’d read his work as an undergraduate. Um, I didn’t always agree with what he, I mean, it sounds ludicrous that a 20-year-old or 21-year-old said, I would say, I didn’t agree, but I had questions about some of his writing, but I knew he was a great mind and, uh, an important figure. And I really desperately wanted to study with him at Yale and I accepted admission to Yale. Then I learned, um, late in the day from Dean David Truman, um, who was then Dean of Columbia College, very eminent political scientist, that I had been awarded a fellowship, the Euretta Kellett Fellowship, to spend time in Oxford or Cambridge. And, um, I ended up in Cambridge. My idea was that I would study for one year in history, was no political science really to speak of in the, the American sense, then, in Cambridge. I would study, um, history for a year, earn a second BA and then go back to America and study with Bob Dahl. But then I got hired as a research assistant by a wonderful historian who worked on Europe and on sovereignty named, uh, F.H. Hinsley, Harry Hinsley. And he sent me to The Hague to look at some, uh, League of Nation Papers. I went and he showed up one of the days I was there, we had lunch. And he said to me, “Ira, I thought Americans are meant to be efficient.” Um, uh, I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “You have a BA, why are you getting another BA, but why don’t you just transfer and get a PhD here in Cambridge?” I said, “Well, I’m going to Yale next year. He said, “Oh, I don’t think you’ll do well in an American graduate, uh, school.”

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: I said I was taken aback. Um, I thought, I, you know, he had hired me, must think reasonably well of me. He said, “I can tell you’re a child of the New Left and of the sixties. You don’t like authority.”

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: “And if you go to graduate school at Yale, you’ll have to take two to three years of coursework, as you did as an undergraduate, get grades each time and so on. Um, but if you stay at Cambridge, um, and if you’re admitted to do a PhD, then, um, you can start your dissertation immediately while you simultaneously attend seminars.” And I thought about it and I thought, “I’ll try that.” And I did, and I don’t regret it, but I deeply miss, uh, having, uh, studied with, with Bob Dahl, whom I later came to know reasonably well. And, um, uh, had chances to share work in draft with him, and, um, but not the same as, uh, as it would’ve been, had he been my dissertation, uh, supervisor. So I, I earned a PhD in history, but I knew that I only wanted, at that point, to teach in a political science department and with the, um, audacity of the ignorant, I only applied for jobs in political science. And, um, I, I had three options. One of them was to come to Columbia as an assistant professor. Um, I believe, to this day, I owe that to my, our late colleague, Joseph Rothschild, who had been my, uh, advisor as an undergraduate from freshman year on. Um, and I’d stayed in touch with him and explained to him why I wanted to be a political scientist, more relevant, more policy oriented, more political, but wanted to do it, um, in a manner that could draw on historical information.

Fredrick Harris: Mm-hmm. Oh, that’s interesting. So before we get to your return to Columbia, uh, what was your dissertation on?

Ira Katznelson: I wrote a dissertation, a comparative study of political responses to Black migration, south to north in America, between 1900 and 1930, and West Indian migration to Britain after 1948. And the central idea was that in both cases, um, you had migrant groups moving from colonial or quasi-colonial, uh, situations in which they were not, certainly were not full British or American citizens. Um, they were formally, they had citizenship affiliation, um, but they were moving to, uh, to, um, participatory liberal democracies in which they could vote. And my question was how, uh, were they incorporated in the polity on arrival? And so that was a study of the very uneven and limited ways in which African Americans in fact were incorporated, um, into both urban and national political life in both countries in this first period of migration, structurally equivalent, but temporally, um, separated.

Fredrick Harris: Right. And it became the basis of your first book, Black Men, White Cities: Race, Politics, and Migration in the United States and Britain.

Ira Katznelson: It did. Correct.

Fredrick Harris: What was the experience like of, rather, uh, having your former professors as your colleagues as you returned to Columbia?

Ira Katznelson: Well, I ,I’m, there’s a big smile on my face.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: Um, it was complicated. Um, uh, I owe an enormous debt to a small number of, of colleagues, alas, none still with us. Lewis Edinger in comparative politics, Harvey Mansfield, Sr, in American politics, uh, Julian Franklin in political theory. I was all of 25 years old. I’d look like a member of the red brigades. Um, and, um, these colleagues treated me as if I belonged. Um, and that was a great boost, uh, uh, to me, but remember I majored in history.

Fredrick Harris: Right, right.

Ira Katznelson: Um, I took some courses in political science, but not many. And the, the truth of the matter is I, I was, um, ill-prepared, uh, to be a professor of political science. Um, I majored in history at Columbia, I took three political science courses. Um, I took no political science courses as a graduate student, and there I was, a professor, assistant professor of political science. So I was running one week ahead of my students inclu, especially my graduate students, um, when I started, but those years at Columbia, followed by a decade at the University of Chicago, um, in effect, was my period as a graduate student in political science.

Fredrick Harris: This feeds into my next question. You left New York and you headed west to the University of Chicago. Now, Chicago’s political science department at that time was among the leading departments in the nation, if not the world. Um, its esteemed faculty included or had included leading figures in the field. Um, Harold Gosnell, Sidney Verba, James Q. Wilson, Theda Skocpol, Jane Mansbridge. And I can go on and on and on.

Ira Katznelson: On and on. Yes.

Fredrick Harris: What attracted you to Chicago? You had done research on the city, including, as you said, you had written a senior thesis at Columbia on the 1919 race riot and in the city and your first book, Black Man, White City, was also based in Chicago, part of it. Is that what encouraged you to move to the city of big shoulders? Your research?

Ira Katznelson: Uh, I think there were two, um, features that, uh, or realities that led me to Chicago. The first, you’ve already articulated. Um, I looked at that faculty and when I made a, I went out for a job interview visit and met, um, this extraordinary group of vibrant, argumentative, sassy, interesting people. I thought, “Wow.” You know, especially for someone who still was an amateur in the discipline, what an opportunity. Um, and second I, as you said earlier, I’m a New Yorker. Um, I love New York. I was- grew up mostly in Brooklyn, I went to Columbia in Manhattan, I was teaching at Columbia and then I, and um, uh, newly married, my new wife, um, we said to each other, “If we don’t move out of New York now, we never, ever will experience anything else.” And um, Chicago, even though for a New Yorker, it seems a bit like a hick town, um, it’s really a great city, interesting city, so let’s, let’s have a go at it. And um, and, and, uh, it was a wonderful decade at the University of Chicago.

Fredrick Harris: Mm-hmm. You’re not the first new Yorker to refer to Ch-Chicago as that. And so I’ll leave it there [laughter]. But while at Chicago, you authored an important study, a book called City Trenches: Urban Politics and the Patterning of Class in the United States. The book explores the resurgence of community activism in the sixties and argues that the American working class perceives workplace politics and community politics as separate and distinct spheres of activism. From your perspective, years later, what do you think is City Trenches lasting contributions?

Ira Katznelson: Well, uh, it, it, it sounds too, um, self-congratulatory, to say, I think the core argument, uh, was correct, um, but let me back up half a step. Um, I got to the question of what might be called- many call, uh, “working class formation” um, out of, uh, a study I was doing in my, I started in my last period at, in, in that moment at Columbia, before I moved to Chicago, um, observing very carefully, um, the politics of community, uh, the politics of conflict, the politics of ethnicity and race, and the politics of class, as it were, in Northern Manhattan in Washington Heights. Um, and much of that book is based on a community study. And what struck me, um, surprised me, was the, the implicit mutual understanding between the insurgents of the period and the authorities of the period, from the mayor on down, of what was at stake in urban political conflict. It was about services, geography, community, ethnicity, um, but it was not about work. It was not about employment. It was not about the labor issues that unions were, uh, struggling about. And at this point, the unions like UAW and steelworkers, et cetera, were still quite strong, much stronger than they are now, um, in, in America. So my question was, “Why this shared understanding and from whence does it date?” And that drew me back to pre-Civil War America in which I ended up arguing that the, it was the early franchise of, um, uh, white men that, um, produced a, uh, separate understandings, um, based on the growing separation in geography between where people worked and where they lived, so that, as citizens, um, where you voted, where you lived, in a world of ethnic solidarities, um, and the like, and, um, separately, you had a workplace set of relationships and I contrasted this with Britain in this period, where the working class at this moment, 1820s, thirties, forties, the vast majority, could not vote. Certainly women couldn’t vote in both countries, um, but men, white men, um, and some African Americans in America could vote. Um, and, uh, but not in Britain and therefore, in Britain, exclusion from full citizenship where you lived, where you would have voted, was understood as a class exclusion. And that meant that class became a more holistic category than it was from early on in the United States. And later in the late 19th century and then again, in the 1930s, when you get moments of the growth of the AF of L and then the CIO, they adopted this laborist orientation, as opposed to a more inclusive class orientation.

Fredrick Harris: So it’s interesting because you, you didn’t do this study in Chicago as, as many of your colleagues at the University of Chicago had centered their research in the City of Chicago. You did it in the multi-ethnic neighborhoods of Washington Heights and Inwood. Um, in Upper Manhattan. So if you can, tell our listeners how you think your findings in City Trenches might have been different, had your case study been in Chicago, the city of big shoulders, the authoritative figure, um, known as, um, Mayor Richard Daley, Sr, um, rather than in, than in the communities based in New York, rather.

Ira Katznelson: That’s a great question. Um, and I actually thought about it quite a lot at the, at the time and since. I think if we were thinking about the white working class, um, I would’ve reached the same conclusion, but in Chicago, the patterning of race, um, was more- it was important in New York, but more overwhelming, um, in Chicago. And in City Trenches, I did argue that the circumstances of, uh, African Americans in New York were different than those I was describing for white residents, because race was a holistic category. Um, in Chicago, um, race in local politics was more quickly, I would say the central defining, uh, quality that divided, um, Person A from Person B. Um, uh, I was there when Harold Washington was elected mayor, and that was a, um, a social movement mobilization of those who’d been left out of the Daley, uh, years. I might say, as a footnote, I had, uh, I don’t know if I’d call it a privilege, but I, I met, uh, father, the Senior Mayor Daley a year before he died, um, in City Hall, uh, in Chicago. Um, and, uh, it was as part of a course, I was, uh, helping to teach at Northwestern for journalists. Um, and he asked me to stay after the journalists left, when he knew, I taught at the University of Chicago and he said to me, “You’re not from, uh, Chicago.” I said, “Um, no, sir, I’m from New York. He said, “I’m gonna tell you why New York has a fiscal crisis, but not Chicago.” And he pulled out the, the budget book of the City of Chicago, um, hundreds of pages in the old green and white, um, computer paper, which is now gone.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter] Right.

Ira Katznelson: And, uh, he turned to a page of tree cutting service. And he said, “In New York, when, um, when tree cutters and trimmers go out, there are four men on the truck. In Chicago, there are two. Um, and there are four in New York because in New York, unions, uh, control the mayor. And in Chicago, the mayor controls the union.”

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter] That’s an interesting story. And also, for our listeners, Harold Washington was the first Black mayor of Chicago. So, um, Ira, you have published many books, and published in several fields in the discipline: urban politics, comparative politics, and political theory and so our discussion this afternoon will not hit all the “Greatest Hits,” but mostly Dean Harris’ favorite books of yours, which leads me to my top favorite, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America. What was this book about and why did you feel the need to write it?

Ira Katznelson: This book, um, was a policy intervention and an offshoot of a larger research program on, um, the role of, um, Jim Crow Southern Democrats in the Democratic Party in the 20th century, especially in the era of the 1930s and 1940s. And as I was doing that research, um, I learned some things I had not known, I’ll come back to them in a second, but I also knew that there was a contemporary debate, a vibrant debate about affirmative action. And, um, I found myself asking, um, whether the contemporary debate, the present-day debate was, um, complete or sufficient, uh, widespread enough. And my answer was that it was not, um, based on what I had been learning in my research. The, the typical debates about affirmative action, um, had on one side, and I’m going to simplify, the argument that affirmative action is a form of compensation or reparations for a long history, going back to 1619, arguably, of, uh, uh, with regard to the Black/white divide. Um, and the opponents of affirmative action were arguing that any racial preference is inherently unacceptable, what we need is colorblind, um, world. And I thought, though sympathetic to the first perspective, um, it was incomplete in a number of ways and I was, um, less sympathetic to the second, but I also thought it was flawed in a certain set of ways. And those two sets of questions, um, collided in the history of the 1930s and 1940s. Remember the Democratic Party in this period, was roughly 50%, um, Northern, uh, labor- and immigrant-oriented, social democratically-oriented, uh, politicians, and Southern, uh, Jim Crow Democrats, um, overwhelmingly not immigrant, um, and, uh, devoted to reproducing white supremacy in the South. My question was, um, what difference did that make in terms of key public policies passed in this extraordinarily important, uh, era of American, uh, public policy making? And when I looked at, uh, the Wagner Act, um, which unions or looked at the Fair Labor Standards Act, looked at the so minimum wage, maximum hours, especially when I looked at the Social Security Act, when I looked at the G.I. Bill, which, uh, transferred more than $115 billion in its first decade to former soldiers of the Second World War, um, by the way, ten times nearly larger than the Marshall Plan, uh, for Europe, in terms of economic transfers, I discovered that in every one of those cases, every single one, Jim Crow Democrats put limits on the access of not all but many, and in some cases, the majority of Black Americans to those felicitous public policies, and they did it in two ways. They did it in some cases by occupational exclusions. So if you were a farm worker or a domestic, a maid, um, you didn’t get Social Security after 1935 until the 1950s. Um, you were not eligible if you worked in those industries, um, for minimum wages or maximum hour legislation just to take those two examples. And why were those jobs excluded? When the Roosevelt administration proposed the laws, they included all wage workers. But in committees, dominated by Southern Democrats, um, these occupational exclusions were put in. And the other mechanism, which we see in the G.I. Bill, was decentralization of federal policies, decentralization of administration. So if you were a Black soldier coming home to Mississippi and wanted a bank loan, which was your right, uh, as a returning G.I., to buy a home or to start a small business, you had to go to your local bank. You wouldn’t get it. Um, and of course, uh, college tuition was being paid for under the G.I. bill, but there were more than 50,000 African Americans who returned home to the South, confronted with a segregated higher education system, who found out there weren’t enough places in higher education, uh, because state legislatures weren’t creating those places. Whereas they did create those places for white, uh, veterans. And hence the title of the book, uh, When Affirmative Action Was White.

Fredrick Harris: Right. So let’s switch a bit, you, you also wrote a mammoth study on the Great Depression. Um, the book is titled Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time. The book has been described as scholarship that examines the New Deal through the lens of a pervasive, almost existential fear that gripped a world defined by the collapse of capitalism and the rise of competing dictatorships, as well as a fear created by the ruinous racial divisions in American society. There have been many books written on the Great Depression, and the bundle of government programs and actions known as the New Deal that prevented total economic collapse during this, this era has been very well documented. So how is your book, Fear Itself, different in its telling of the impact of the New Deal compared to other studies about the era?

Ira Katznelson: I think the book, um, at least in my imagination, um, is distinctive in a, in a small number of ways, but they reinforce each other. First, I treat the full 20-year history of Democratic New Deal/Fair Deal rule of Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, as a single long, uh, period, um, that both transformed domestic public policy, but also the global role of the United States. And that’s a second unusual feature of the book, which is most, uh, studies of this period, either separate out the thirties and the forties and they almost always separate out global relations from domestic politics. I’ll come back to that. And third, um, and third, I privileged the, um, again, the role of Southern Democrats in the making of policy, both domestic and international, treating the American political system in this period, as, in effect, a three-party system: Republicans, Northern Democrats, Southern Democrats. Those three aspects together: the longer timeframe, the refusal to separate out domestic and international, and the focus on law-making and the role of the very odd constellation of, uh, partisanship in Congress. It’s a Congress-centered book, um, which is, of course, also a bit unusual because most of the studies of that period are Presidency- Roosevelt-centered or Truman-centered. Um, those together created an analytic, um, framework in which I could end up saying some things that I wanted to say or explain. And I’m happy to, um, to say what I think the object of analysis was and why those, um, analytical choices, uh, help designate understanding of the, of the outcomes I have in mind.

Fredrick Harris: I’m struck by the title, Fear Itself, in thinking about the present crisis where, we’re, you know, ending hopefully a global pandemic, which has intensified, uh, racial hatreds and exacerbated economic and social inequalities. Um, can you speak to how Fear Itself speaks to the current crisis we’re experiencing?

Ira Katznelson: Yes, but of course, uh, uh, as we, as you well know, the, the phrase “fear itself” appeared in Franklin Roosevelt’s, uh, inaugural address of March, 1933. And, um, I think what was so critical about his emphasis on fear, it was that this period was marked, as perhaps the present is, by layered and multiple sources of, uh, of fear. Um, and by fear, I mean, having to confront a circumstance where the status quo or recent history is an insufficient guide. Well, in the thirties, what was so striking was the growth of regimes in Berlin, uh, in Rome, in Moscow, each of which claimed to be a better democracy than the liberal democracies, cuz they were more direct, um, party-led, um, single-party-led, um, voices of “The People,” the working class in, in the Soviet Union, the German “Race,” uh, the Italian nation. And it was the job of, uh, the New Deal and the Fair Deal, in part, to counter that and say, “No, actually, we can solve problems, big problems, we can conquer, we can conquer fear. So that’s one of the, the, the threads and the other of course was at home. This is still a period where lynchings are occurring. It’s a, um, uh, a moment of, uh, extraordinary, um, uh, ugliness in terms of, a racial dimension, not that there was no racism in the North, of course there was. Um, but the Southern form of expression was more virulent, more violent and more backed by local law. Um, and the representatives of that system had incredible power in Congress. So there’s a great irony that the, the answer to globally generated fear, political fear, which the dictatorships were generating, the responses, um, were made, I would say with disproportionate power by, um, the representatives from what were then 17 states of the union that practiced legal racial segregation.

Fredrick Harris: Right. Right. I want to continue a bit on that theme. Uh, you have recently written, in a personal essay, that one of the unifying themes of your scholarship has been the conditions that influence the state of liberalism and democratic societies. As you note, the kinds of questions that you have pursued in your body of scholarship examines “under what conditions is liberalism to be more open or more closed, more egalitarian or more hierarchical, more secure or more vulnerable.” Can you say more about your intellectual project on liberalism over all these years?

Ira Katznelson: I would say, uh, uh, that from the very start and I, here I go back to the inspiration of Richard Hofstadter and Juan Linz, among other teachers when I was an undergraduate and then others, uh, uh, along the way. I’ve come to appreciate that, um, the ‘liberal’ in liberal democracy, as a set of conceptual ideas: rule of law, government by consent, political representation, um, et cetera, this kind of conceptual apparatus is not one any of us would want to live without. We do not want to live in a world without rule of law, without rights, without representation. Um, but li- liberal democracies are not just ideas, they are actually existing places, that have a long history of, um, non-inclusion, of exclusion of, um, creating divisions between those who do enjoy rule of law, rights, and representation, and those who do not, uh, as one set of examples. And then of course, liberal, all liberal democracies are, are states in a world of states and then have to take care of national security. And doing that, um, they’re always at the boundary of the illiberal, as well as the liberal. Questions of secrecy, questions of surveillance, questions of loyalty, um, which sometimes appear as they did in the McCarthy period, in particularly brutal form. But those questions are always there. So I think we cannot do without the ‘liberal’ in liberal democracy, but how, in historical and actual reality we live with and through liberal democracy is an open question. And, um, that’s a question, not in my mind, about whether we should wish to have a liberalism pair with democracy, but what kind of liberalism we should wish to have. And I think almost everything I’ve written from one angle or another has had that implicit or explicit question, uh, underneath, uh, the given text.

Fredrick Harris: How much is the United States experiencing in terms of an illiberal period in its history? Or if we can call it history cause it’s, it’s ongoing, it’s contemporary.

Ira Katznelson: Ah, well, it- it’s, uh, what a profound question. No two- or three-minute answer will do it justice. The United States, in some fundamental way, um, from the Revolution on, was a politically liberal regime, um, for those who were included, I’ll answer it this way: in the great work by Alexis Tocqueville- de Tocqueville, uh Democracy in America, Volume One, published in 1835. So the United States is not very old. Uh, some, you know, six decades, um, Tocqueville has this brilliant last chapter of Volume One called “The Three Races in America,” white, Black, red in his depiction, uh, Native, Native Americans, African Americans, white Americans. And he begins the chapter by saying, “Until now, I’ve been writing about democracy in America and implicitly liberal democracy and now I’m turning to another subject, um, the subject of race, exclusion, violence, even, he predicts, genocide, um, with respect to Native Americans. Um, but they’re not separate subjects. Um, and I think what we need to understand is the conditions under which liberal democracy, by its very character opens up ugly prospects, because it’s a system of rights and representation for those who have it. And if civil society wishes to exclude or to brutalize, politicians, um, get pressure to do just that and to, win votes on those platforms. We can see that today in, um, in, in much of our politics. Uh, why is the Mexican border, um, so central to the MAGA side of the Republican Party? Um, why is resistance to, um, uh, Black Lives Matter so central to the politics? It’s the very structures of liberal democracy, which we would never want to do without that also opens the door, as it has from the beginning of the Republic, um, to patterns of limitation and exclusion. Uh, we might remember that the first, uh, immigration act passed in American history in 1790 was for white people only explicitly. They were the only ones who could come to America and quickly become citizens. So America has both been a liberal and illiberal democracy, um, from the beginning. And the question is, um, what were the dynamics of continuity and change over time? The United States today is not identical to what it was 50 or a hundred or 200 years ago in these dimensions, but we have not solved, um, the dilemmas of illiberalism in the American experience.

Fredrick Harris: Let’s briefly, uh, switch gears and talk about your experience as an administrator. Um, you served as Chair of the Political Science Department at Chicago, and you eventually returned to New York as the Dean of the Graduate Faculty at the New School for Social Research. You later returned to Columbia and since your return, you have served as the Interim Executive Vice President for Arts and Sciences, President of the Social Science Research Council, and most recently, Interim Provost of Columbia. You are perhaps the only person I know who has figured out how to balance high profile administrative duties with a productive, and I might say, robust research agenda. Um, Ira, do you ever sleep?

Ira Katznelson: [Laughter] Well, notice the word ‘interim’ in two of those jobs.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: Um, I refused in these cases to, um, do more than a short-term service, but, look, I love universities and I, and I think the work we do as, um, as scholars, has great value potentially as democratic reason. Um, uh, so the fields in which you and I work, Fred, um, and I think as much of your work as mine, but that of many of our colleagues, um, help strengthen, um, values we hold dear and contributes to the balance between what a moment ago we were calling, uh, together, uh, liberal versus illiberal democracy. It strengthens the liberal side. Um, we practice forms of liberal knowledge, open knowledge. Uh, we debate knowledge. We have norms of reason about knowledge. We have evidence in our knowledge, we have methods in our knowledge. It’s a privilege, from time to time, uh, to help, um, administer, guide, govern, uh, what’s the right word? Basically work with colleagues to change probabilities within the university or within disciplines, that excellent things can more likely happen. And that’s the appeal of an administrative job. The longest I’ve ever done anything like this is a five-year run, uh, at the SSRC, but it was not a full-time job. It was defined as a 50-50 job, it really was more than 50-50, but it was defined as such and I continued to teach at Columbia and I, I published Fear Itself during that period of, um, uh, much of it had been finished at the beginning, but, um, uh, as I went. When I was an Interim VP for Arts and Sciences, I did it for, for one year. Um, uh, and I was a dean for, for seven and a half years at the New School, but I was never a dean, it’s a small institution, before one o’clock in the afternoon.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter]

Ira Katznelson: Um, so, um, there we are, I’ve tried to have it both ways. [Laughter] I feel that I’ve been enriched by having had these opportunities, I’ve met people I never would’ve known, um, and I’ve learned something directly about institutions and organizations that would’ve been, uh, more abstract for me, um, had I not had these, uh, opportunities.

Fredrick Harris: Right, right. So finally, I would like to end with a story and a question. So sometime in the late eighties, I first encountered the name Ira Katznelson. I was a research assistant to the now late Linda Faye Williams,

Ira Katznelson: Ah.

Fredrick Harris: one of your former graduate students, Ira.

Ira Katznelson: Yes.

Fredrick Harris: Um, and I was a research assistant at the Washington think tank, the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. I did not know then, but Linda was prepping me for graduate school. And she often told me great stories about her adventures as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. The stories usually came with a lesson or two of “dos” and “don’ts”. So once, Linda mentioned her dissertation advisor, Ira Katznelson, whom she adored, but noted that it was always hard to reach Professor Katznelson over the summer break, because he spent his entire summers in Cambridge, England. I have to ask this question: why your fascination with Cambridge, England, Professor Katznelson?

Ira Katznelson: Well, wonderful. First of all, um, remembering, uh, Linda Williams is an honor and a treat. She was an extraordinary person, and to learn that she helped guide you, dear friend, um, into the world of, uh, social science, um, makes me deeply, deeply, deeply happy. Um, there’s a kind of, uh, long run, uh, continuity of relationships here which is, uh, deeply pleasing. Um, well, as, as already mentioned, I, uh, I did my graduate work there. Um, I also made many friends there, including in the discipline of history. Some were my teachers, others were fellow students, and, but I left, uh, I didn’t go back for some time. Um, uh, certainly not for five or seven or eight years, uh, after getting my PhD. And then I was invited back, um, uh, to give a series of lectures and, uh, went and realized just how beautiful it is, but also how much, um, good work I was able, I think, to achieve in the great university library there and with colleagues. That’s Part A. Part B is my only adult experience with, um, antisemitism, uh, serious experience. My family was already spending summers in rented accommodation most summers in Cambridge, but we had moved to New York from Chicago and decided it would be great if we could only find a country place outside the city, but anything we could afford, um, uh, was, was not very nice and what we liked, we couldn’t afford, but suddenly an opportunity arose in a housing association, um, about an hour and a half north of the city in the Hudson Valley. And we went, we looked at a spectacular house, it was affordable. We had to be interviewed by the housing association and the housing association rejected our application. I, I could tell the story in a much more dramatic, long way on a five to four vote, because it was thought that if, um, persons of our background were admitted to this small community of 11 houses, uh, the neighborhood would tip, um, and we would only bring in other people of our religious and, uh, ethnic background. And that next week I found myself again in Cambridge, um, and friends said, well, we, I told them the story. They said, “The answer is: get a house in Cambridge. You’ll use it every summer.” We found the house for a modest amount of money and a lovely house in a lovely place and have been using it, um, for summers, um, ever since, for decades now. And we’re, and I get a lot of writing done there, library research, wonderful friends, London is not far, great theater, great music. Um, it’s been a counter, a counterpoint to New York, a very privileged one, um, [laughter] in, in my life, But, um, like the original decision to do graduate work in Cambridge, it was, uh, something of an accident or certainly unplanned, um, but I don’t regret a minute of it. And this year I’ve been on leave following my, um, stint in the Provost’s office. Um, so I’ve spent most of it, uh, trying to read and write and getting back into rhythm, academic rhythm, um, uh, in the U.K.

Fredrick Harris: Yeah. Well, I, I, I look forward to that, um, that is, uh, getting back into the rhythm, um, once I step down as Dean, but, but, um, thanks so much, Ira. This has been a, uh, a terrific conversation.

Theme outro music

Ira Katznelson: Thank you. And we can’t wait to have you back fulltime, um, uh, as Scholar Harris in the Department of Political Science.

Fredrick Harris: [Laughter] Thank you so much.

Now to our listeners, this is the last episode of The Dean’s Table, at least my last as Dean of Faculty in the Social Sciences. After five years as Dean, I’m going on sabbatical for a year to finish and start book projects that have been long to neglected. Um, my plans are to return to the faculty year after next, and continue to teach and write. It has been a joy to interview and get to know some of my colleagues in the division more intimately. It is my hope that the podcast will continue on my return, perhaps as The Podcast Formerly Known as The Dean’s Table. Well, we’ll see, Until then, all the best.

The Dean’s Table is produced by Eric Meyer, with production assistance by Jack Reilly. Our technical engineers are A.J. Mangone, Airiayana Sullivan, and John Weppler. Our researchers are Emma Flaherty and Angeline Lee. Our logo design is by Jessica Lilien, episode portraits are by Cat Willett, and our theme music is by Imperial. I’m your host, Dean Harris.

Latest Episode

Sociology Professor Mario L. Small – DT014

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 54:44 — 125.3MB)